by

[user not found]

| Jul 10, 2015

A successful Lean implementation is one of the most trying and challenging things a company can embark on. It’s a demanding experience for both management and employees. It requires a whole team of people seeing the possible end goal and believing that this transformation is one for the better. For the average organization, that’s a tall order.

Failure rates of Lean implementation are staggering. One study from iSix Sigma found that failure rates of Lean implementations, conservatively speaking, hover around 50 percent and can balloon as high as 90 per cent (failure defined as a return to the organization’s original way of doing business) Statistically speaking, there’s a real chance your company won’t make it through the first year of Lean.

Failure rates of Lean implementation are staggering. One study from iSix Sigma found that failure rates of Lean implementations, conservatively speaking, hover around 50 percent and can balloon as high as 90 per cent (failure defined as a return to the organization’s original way of doing business) Statistically speaking, there’s a real chance your company won’t make it through the first year of Lean.

That being said, that doesn't mean hope is lost.

Lean is a very possible to implement but far from simple. Us at VIBCO, for example, began Lean in the early 2000s when it became apparent to us that our current system of manufacturing our vibrators and making deliveries and fulfilling orders on time was not sustainable. The changes that needed to take place were dramatic and pressing. Management was working over time learning the language of Lean and serving as the beacon of where to go and how to keep the company focused and engaged. 10 years later, we’re still invested in the cause and continuing to improve. When we host Gemba Walks and tours throughout our factory, we insist to those on the tour that we are far from finishing our Lean journey and it is (and was) far from easy.

Successful Lean implementation case studies are finite but they do exist, validating the belief that a successful Lean transformation is possible. It’s these case studies that help to shed light on just the kinds of trials and tribulations that an organization must endure going through the implementation, the work required before the implementation to acclimate and familiarize the company with what’s around the corner and the work after - the act of sustainability and keeping on course towards improvement.

Here are 3 lean manufacturing case studies that highlight how Lean has been successfully implemented.

1. Case Study #1: New Balance

If you've ever walked into a JC Penney or Kohl's shoe department, you've seen the New Balance brand.

Meet New Balance

New Balance is an American shoe and apparel company based out of Boston, Massachusetts with a factory in Lawrence, Massachusetts. The company was founded in 1906 in Boston and began as a manufacturing company for arch supports, later expanding into footwear in the 1960s and later apparel lines including clothes and socks shortly after. The company has remained in the United States and prides itself on its Made in the USA seal and commitment to American manufacturing and Lean as its driving manufacturing compass as of 2003.

New Balance is an American shoe and apparel company based out of Boston, Massachusetts with a factory in Lawrence, Massachusetts. The company was founded in 1906 in Boston and began as a manufacturing company for arch supports, later expanding into footwear in the 1960s and later apparel lines including clothes and socks shortly after. The company has remained in the United States and prides itself on its Made in the USA seal and commitment to American manufacturing and Lean as its driving manufacturing compass as of 2003.

Naturally, the idea of Lean was approached dubiously by New Balance staff. As John Wilson, executive vice president of manufacturing at New Balance explained, "The cardinal rule we made when we started was that that no one was losing his or her job," said Wilson. "If people leave and we don't replace them that are a different story." Part of the challenge of successfully implementing Lean was convince the workers that none was going to lose their job, one of the common fears associated with Lean or any kind of substantial shift in management style and operations.

Lean Education and New Balance’s Start With Lean

To help usher in the idea of Lean to New Balance, the company began holding educational sessions.

Managers from all parts of the company learned lean principles, as well as employees from divisions of the company that one immediately might not think would have any direct association with ‘Lean manufacturing like the accounting staff or design teams. Executives' 30 hours of instruction included a myriad of topics including the foundations of the original Toyota Production System (TPS) concepts, lean product development principles, and value-stream mapping, both the practice of and the theory behind.

Management on the factory floor and those directly affiliated with the day-to-day factory operations got approximately 100 hours of training in areas including TPS, strategy deployment, the plan-do-check-act problem solving cycle, standardized work, and lean leadership.

The Lean Implementation: Action, Struggle and Work

Problem solving periods happened daily and followed rigid timetables. Members of New Balance’s value stream team would meet with supervisors at in the morning. for production meetings at the stream's designated problem solving location. Members would also meet with also meet with quality assurance engineers on the shop floor daily between 9:30 a.m. and 10 a.m. to review quality issues.

Problem solving periods happened daily and followed rigid timetables. Members of New Balance’s value stream team would meet with supervisors at in the morning. for production meetings at the stream's designated problem solving location. Members would also meet with also meet with quality assurance engineers on the shop floor daily between 9:30 a.m. and 10 a.m. to review quality issues.

As one profile piece on the New Balance Lean transformation from the Lean Enterprise Institute details, “during twice daily audits, each team's coordinator uses a check sheet while observing whether operators are following the step sequence for their processes within takt time. Supervisors spot check that the coordinators' audit sheets are up to date”.

Sustainability is one of the most challenging aspects to a successful Lean transformation. New Balance remedied this by routinely reviewing results from teams operations and reports and charted the findings from one meeting to the next. Additional follow-up audits or reflection times are often scheduled.

New Balance’s biggest problems were with batch and queue processing and extensive works-in-progress. Prior to Lean, New Balance’s manufacturing process focused on designated stations where specific activities of the product making process would take place. As one station was occupied making a component of a shoe, the other stations were either left with too much work, too little work or no work at all and left waiting for work to come through their space. The batches had long lead times and the inventory required to sustain these large lead times ate into the company’s profit and profit growth potential.

The addition of single-piece flow (or one pair flow as New Balance referred to it) was pivotal to their production. By ending the batch and queue process, New Balance was able to:

-

Remove excessive inventory and free up space in their factories for more machines or employee focused learning areas

-

Improved faster takt times per unit

-

The ability to take on greater order demand without falter

-

Improve lead times and cut production costs

-

and continue to grow as a company and stay competitive with a wholly American made produce

From a business logistics perspective, New Balance needed to change there as well. The company focused on how they were going to fulfill their 24 hour promise, a promise to retailers that New Balance will turn around orders for core style shoes in just 24 hours. "We will ship it in 24 hours from receipt of order," Wilson said from the Lean Enterprise Institute piece. To make sure this promise was met, New Balance made sure it’s core shoe line was made domestically and since it was going to be made domestically and closer to the retail outlets, the application of the aforementioned Lean concepts was all the more critical.

From a business logistics perspective, New Balance needed to change there as well. The company focused on how they were going to fulfill their 24 hour promise, a promise to retailers that New Balance will turn around orders for core style shoes in just 24 hours. "We will ship it in 24 hours from receipt of order," Wilson said from the Lean Enterprise Institute piece. To make sure this promise was met, New Balance made sure it’s core shoe line was made domestically and since it was going to be made domestically and closer to the retail outlets, the application of the aforementioned Lean concepts was all the more critical.

The most popular domestic styles have annual inventory turns as high as 18, New Balance’s domestic plants can generate at least 24 turns of finished goods due to the lean production improvements. Production planners were able to see what customers are buying by electronically monitoring what shoestyles, sizes, and widths the distribution center has shipped to retailers during a one to five day period.

They schedule production to replenish what's been shipped, maintaining a level of finished goods to provide a 98% "at once" availability to retailers.

The ideal level of finished shoes inventory is as low as possible without running out. "It's easy to have 100% availability if you're carrying 200 days of supply," Wilson said. "We're trying to keep finished goods inventory down to 22 days or even lower." Currently some styles are made daily. Most are made weekly, but the company is gradually moving these to daily production as the lean transformation progresses. Planners adjust inventory levels to account for demand spikes in peak months or the introduction of new styles.

Read more on New Balance’s Lean Manufacturing Implementation:

2. Buck Knives

Ever been hunting or know a friend that’s an avid hunter or fisherman? It’s likely you’ve come across Buck Knives. The Buck Knives name has become synonymous with hunting, fishing and outdoor sport much the same way Kleenex has become an interchangeable word for tissue. While the Buck Knives name holds considerable weight in the outdoor equipment market, there was a time when the company was in serious financial trouble and needed a solution.

Meet Buck Knives

Buck Knife as a manufacturing company is unique compared to the aforementioned New Balance shoes, but benefitted none the less from a Lean transformation. As one can imagine, commercial hunting knives require a different manufacturing process than shoes and serve a different market. Buck Knives must overcome creating a safe (accent on safe) high quality knife product with materials that are subject to very volatile price changes and availability and a high learning curve to the knifemaking process itself and a very, very uneven demand (45% of the company’s sales come during 3 months of the year).

Buck Knife as a manufacturing company is unique compared to the aforementioned New Balance shoes, but benefitted none the less from a Lean transformation. As one can imagine, commercial hunting knives require a different manufacturing process than shoes and serve a different market. Buck Knives must overcome creating a safe (accent on safe) high quality knife product with materials that are subject to very volatile price changes and availability and a high learning curve to the knifemaking process itself and a very, very uneven demand (45% of the company’s sales come during 3 months of the year).

Back in 2001, Lean proved to be the best solution to the survival of the Buck Knives company. The combination of the 2001 World Trade Center attacks and the increased cost of doing business in California, the company’s home since it’s inception in the 1940s, Buck Knives was on the brink of collapse. None was buying knives and the cost to make knives was unsustainable. A factory re-location was imminent and a big pivot from the old way of manufacturing was required to keep the company afloat through very trying times.

The first step was to develop for how to survive and move forward. First, the company set out to reduce their costs that began by moving to a state that charges less for energy, regulatory and labor costs (their current location in Port Falls, Idaho), buying a new enterprise resource planning (ERP) system and becoming a Lean-oriented culture. The latter being the most important for long term survival.

Prior to 2001, Buck Knives worked in a way many manufacturing operations tend to work: with a batch and queue model. By this design, the factory floor’s operations were disconnected and left individual stations waiting for the station prior to it to complete its work before beginning on it’s own. Additionally, like New Balance, abundance of works in progress were very common.

Naturally, the first major shift was to assembly cells and away from batch and queue. This was the first step Buck Knives made and the factory workers saw the improvements instantly and became inspired to keep going. Cross training began and leaders from one group trained another who then trained another over the course of several months until the factory floor was completely converted to assembly cells.

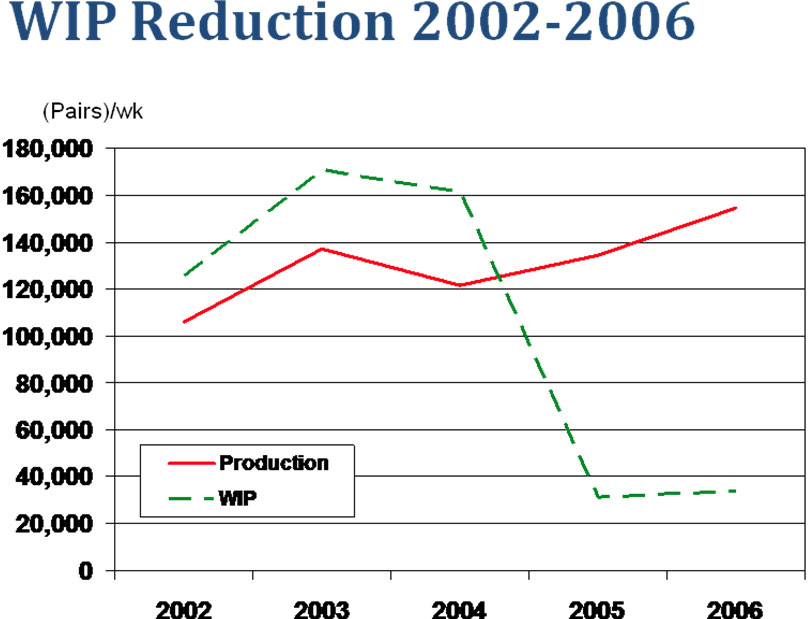

To support the practical application Lean, learning and teaching sessions were held. Experts from around the country were summoned to share their knowledge and insights into the Lean transformation process and to offer insights into how to sustain the positive changes that were already taking place. The overarching positive was a “60% reduction” in work in progress projects.

The sport knife market experiences a very uneven market with large peaks and valleys with regards to demand. To tackle these inconsistent in an already beatdown market landscape, the company began by working to reduce their finished goods inventory to one month’s worth of product but with the ability to ramp up or throttle down production for the fluctuating demand cycles. This way, there was always just enough stock on hand. Buck Knives also began vendor-managed inventory programs with large clients like Walmart and Cabelas. Using Walmart’s 12-month sales totals, the best indicator the company has had for measuring demand, the sales team would then divide the 12-month sum into 10 equal amounts between January and October to determine how much product should be made and kept in stock.

The sport knife market experiences a very uneven market with large peaks and valleys with regards to demand. To tackle these inconsistent in an already beatdown market landscape, the company began by working to reduce their finished goods inventory to one month’s worth of product but with the ability to ramp up or throttle down production for the fluctuating demand cycles. This way, there was always just enough stock on hand. Buck Knives also began vendor-managed inventory programs with large clients like Walmart and Cabelas. Using Walmart’s 12-month sales totals, the best indicator the company has had for measuring demand, the sales team would then divide the 12-month sum into 10 equal amounts between January and October to determine how much product should be made and kept in stock.

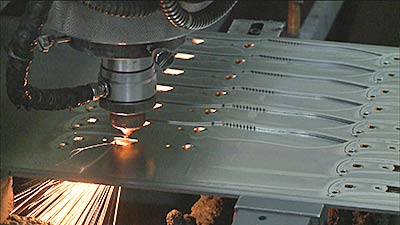

Though our the company’s implementation of lean into their manufacturing processes, wasteful spending was uncovered. C.J. Buck, the company’s CEO, explains that the company uses a specific kind of fine blank machine to cut blades from metal and was faced with having to invest in new customized tooling for the machine to produce a new product. To acquire and equip this machine with the proper tooling usually costs Buck Knives around $80,000 and yields a marginal turnaround time.

Brian Maskell from BMA, Inc., a Lean accounting firm, asked if the company had idle capacity elsewhere that could handle the increased demand. As it turns out they did in fact have something idle: a laser cutting machine, but it cuts blades at the rate of 60 to 80 an hour while the fine blank machine can produce 600 to 800 an hour.

According to traditional-accounting principles, the large-batch option would have been most profitable. But using lean-accounting principles, which favor flexibility over large-batch production, the laser machine was the better option, and that’s what the team chose. The laser machine allowed for smaller batches and save money on not investing in acquiring the needed tooling for the machine.

According to traditional-accounting principles, the large-batch option would have been most profitable. But using lean-accounting principles, which favor flexibility over large-batch production, the laser machine was the better option, and that’s what the team chose. The laser machine allowed for smaller batches and save money on not investing in acquiring the needed tooling for the machine.

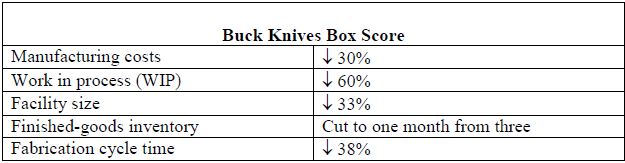

For Buck Knives, Lean came at a turning point for the company. The company was faced with a series of extreme situations at the same time - the September 11th attacks, a national change in the feelings towards buying weapons and specifically sports knives, and an increase in the cost of doing business in California - that shattered the company’s original way of meeting customer demand and forced them to adopt a new way of doing business that could endure these changes.

The results spoke for themselves in a few short years. Buck Knives cut down on excessive machinery, improved lead times, removed excessive inventory and stock product, cut costs and got a company behind the vision.

Read more on Buck Knives’ lean implementation process:

3. Case Study #3: The Wiremold Company

The Wiremold Company still holds the title as one of the best cases of a successful Lean implementation in manufacturing activities.

The history of The Wiremold Company began in 1900. D. Hayes Murphy, a college graduate with an ambition to jump into the manufacturing business. Murphy, along with his father Daniel E. Murphy, became interested in the Milwaukee-based Richmondt Electric Wire Conduit Company, a company that manufactured a special kind of wire conduits. Richmondt’s conduits were zinc-coated, and pipe-like allowing for wires to be housed within them, protecting the wires from wear and corrosion.

While the product was in high demand, the company was inefficiently run, wrestling with difficulties meeting the high demand for their product. Amidst their management issues, the Murphy family confronted management with an offer to buy them out for 10,000 dollars. The transaction lead to what we now know as the Wiremold Company. Since the buyout the company uprooted from Michigan and settled in Connecticut.

Warren Packard and Wiremold Before Lean

The Wiremold Company was not always a beacon representing the ideals of Lean manufacturing come to life. Wiremold came to prominence after Art Byrne become the company’s CEO in 1991. Byrne and then vice president of Wiremold’s finance Orry Fiume who spearheaded the company’s now famous Lean initiative, transforming the company from one that was losing money and running at a fraction of it’s potential to a well oiled, flowing machine increasing sales from 100 million to 450 million dollars in 10 short years up until the company was sold in 2001.

Wiremold’s Lean transition, like Buck Knives and New Balance, suffered from a stagnant, stifling way of doing business. Despite being an international leader in conduit casing, by the 1980s, Wiremold was slowly becoming paralyzed by company inefficiencies. Tools and machines in the factory were and the company was quickly being matched by competition and unable to respond quickly. It was taking too long to get new products to market, deliveries were lagging, customer service was declining, and overall growth was falling off.

Under Warren Packard, Wiremold’s company treasurer since 1973, Wiremold launched several initiatives aimed at righting the ship, including a first stab at implementing a Japanese style just-in-time production system. The initiative failed. Equipment failures unable to maneuver the new expectations to personnel difficulties with the idea of increased production on that scale. Moreover, employees were hesitant and apprehensive to the idea of change and let the idea go slack when it was left to them to carry on. Packard soon realized that himself realized the company needed a new leader to make the sort of fundamental changes which would spark a turnaround.

He thus announced in early 1991 that he planned to retire and then led the search for his replacement. Late in the year Art Byrne was hired on as the new CEO.

Byrne, Fiume and Wiremold’s Lean Transformation

Art Byrne joined Wiremold years of experience as a group executive with the Danaher Corporation, where he had successfully made use of kaizen to improve the company’s factory floor processes and manufacturing operations. At Wiremold, in an unusual theme uncharacteristic to Lean but consistent with Packard’s belief that the company needed a fresh start, Byrne first reduced the workforce, offering early retirement packages to unionized workers and implementing a modest layoff of salaried employees.

Art Byrne joined Wiremold years of experience as a group executive with the Danaher Corporation, where he had successfully made use of kaizen to improve the company’s factory floor processes and manufacturing operations. At Wiremold, in an unusual theme uncharacteristic to Lean but consistent with Packard’s belief that the company needed a fresh start, Byrne first reduced the workforce, offering early retirement packages to unionized workers and implementing a modest layoff of salaried employees.

Byrne then encouraged management to join him in replacing the traditional hierarchical system of management with a more ambitious team-based model. As Byrne saw it, the team structure provided the important framework for his implementation of both kaizen, in which small groups participate in problem-solving sessions, and just-in-time manufacturing as well as to encourage management to go to the gemba with their fellow co-workers rather than sit perched above the day-to-day fray. Within a few years the manufacturing process had shown a steady stream of improvements, and both defects and inventory were dramatically reduced.

Kaizen, Byrne’s biggest asset at Wiremold, spearheaded many of the changes. While kaizen workshops on the production floor attacked long lead times, delays, batching, wasted space, and poor material and information flow, kaizens in the tooling department attacked the same problems in tool maintenance, design, and fabrication. Management as well as floor workers were involved in kaizen. The mindset became lasting at Wiremold, shifting away from ‘doing kaizen’ - implying a start and end point to kaizen - to always being in a state of kaizen where employees as well as management were encouraged to act on their ideas in the name of improvement.

The results spoke for themselves. Productivity at Wiremold improved by 20 percent in each of the first three years.. Between 1991 and 1995, inventory levels were reduced by more than 75 percent. The time to develop new products was reduced from three years to less than six months. Sales, wages, and profits were all growing at a substantially greater pace, with revenues doubling from $100 million to $200 million between 1991 and 1995. As a result of the lean techniques that Byrne had championed, Wiremold became a model to be emulated, its turnaround story told in the books Lean Thinking (1996) and Better Thinking, Better Results (2003).

The newfound company performance and skyrocking profits opened up new doors for Wiremold in the way of acquisitions to improve the company’s supply chain and introduce new products. Perma Power Electronics Inc., a producer of super suppressors, line conditioners, and uninterruptible power supplies was acquired in 1993 as was Walker Electrical Products, a manufacturer of in-floor and overhead systems for distributing power, lighting, and communications. Raceway Components, Inc., the leading brand of poke-thru systems, which provided invisible wire and cable management for open-space areas was acquired in 1995.

The kaizen approach also aided new product development efforts. One of the newer introductions came late in the 1990s when Access 5000 decorator raceway debuted. This nonmetallic multi-channel raceway came in a selection of finishes, including real wood veneers, thus offering a combination of architectural trim and cable and wire management in one package. By 1999 the acquisitions and new products had helped revenues double yet again, to approximately $400 million.

Byrne embodied the often overlooked Lean pillar respect for people. While most managers beginning on a shift towards Lean focus on the idea of improvement and cutting waste, Byrne focused not only on those ideas but making sure his employees were listened to and respected throughout the process. Moreover, Byrne’s methods for exercising this idea were far from complicated. Byrne simply included everyone in kaizen, elected strong leadership to kaizen, empowered his employees to act if they saw something needed change and provided positive reinforcement when something good changed. He encouraged his team to learn by doing and going to where the work was done and the money was made for Wiremold in the name of perspective and understanding. He challenged his employees with a tone and demeanor that was less ‘do this now because I said so’ and more ‘I believe you can do this because you are a skilled, competent individual’. The change in tone and delivery made all the difference when communicating and striving to bring a team to new levels of insight and action.

The 1990s were a fantastic time for Wiremold. The company was the talk of the Lean world and crowned as the best implementation of Lean in an American business and sought after by business leaders for guidance and insights. However, by the start of the next decade things turned sour for the company. In 2001, Wiremold was bought out by a French competitor company Legrand and the Lean improvements championed by Fiume and Byrne were halted. Legrand purchased Wiremold believing this immense profitability was self-sustaining and would continue even with the change in management. They were wrong.

Micromanagement returned to Wiremold, employees were not encouraged to act and study as they were under Byrne and, worse, the batch and queue model of manufacturing returned. The Lean improvements were thoroughly undone within a few short years of the acquisition and the company was returning to a pre-Byrne workflow and profitability.

Art Byrne, since his retirement from the company in the early 2000s, has spoken extensively on his time with Wiremold, sharing his learning experiences and insights with thousands of other business and organization leaders around the world. While Wiremold remains a part of Legrand to this day, there aren’t as many clear examples of what happens before and after a Lean transformation as well as what happens when a company gets behind Lean in every way - from management to janitors.

Read more on Wiremold’s Lean implementation case study:

Wrap Up

Lean is difficult, but far from impossible. From a theoretical perspective, it’s fairly easy to understand the idea behind the concepts and the tools. From a practical application perspective, the action is vastly different.

Many companies struggle with Lean and achieving a successful Lean implementation and make the mistake of believing there is an end to the journey. There isn’t. VIBCO still considers itself on a Lean journey. Every day it’s staying on point with the ideas of watching out for the 7 (some say 8) wastes, respecting the ideas of those around you and for management keeping up with making sure that your company has their eye on the end goal.

These are a few of the case studies that have stood out as remarkable in the world of Lean implementation. All these companies had a certain way of doing business but it wasn’t until something came along that was going to jeopardize the future of the company was a change made. Each of these companies had a top down management style, processed good batch and queue and, without knowing it, were working at a fraction of their potential. For all these companies, including VIBCO, it wasn’t until some massive event occurred that caused management to realize that a change needed to be made, rally the company behind a cause and go forward.

It’s very easy to talk about Lean but it’s very difficult to implement it, but with a management structure willing to hear some new ideas, a team ready to get to work and a whole lot of commitment coupled with the understanding that it’s going to be a trying experience and it’s going to be difficult, any company or organization can undergo a successful Lean transformation.